How To Spot a Faker

Four things fakers do (and don't do)

Vishal: You were saying that fakers misrepresent themselves to gain social status.

Bill: That’s right. Enhancing their social status is what fakers aim to do.

Vishal: How do fakers go about doing that?

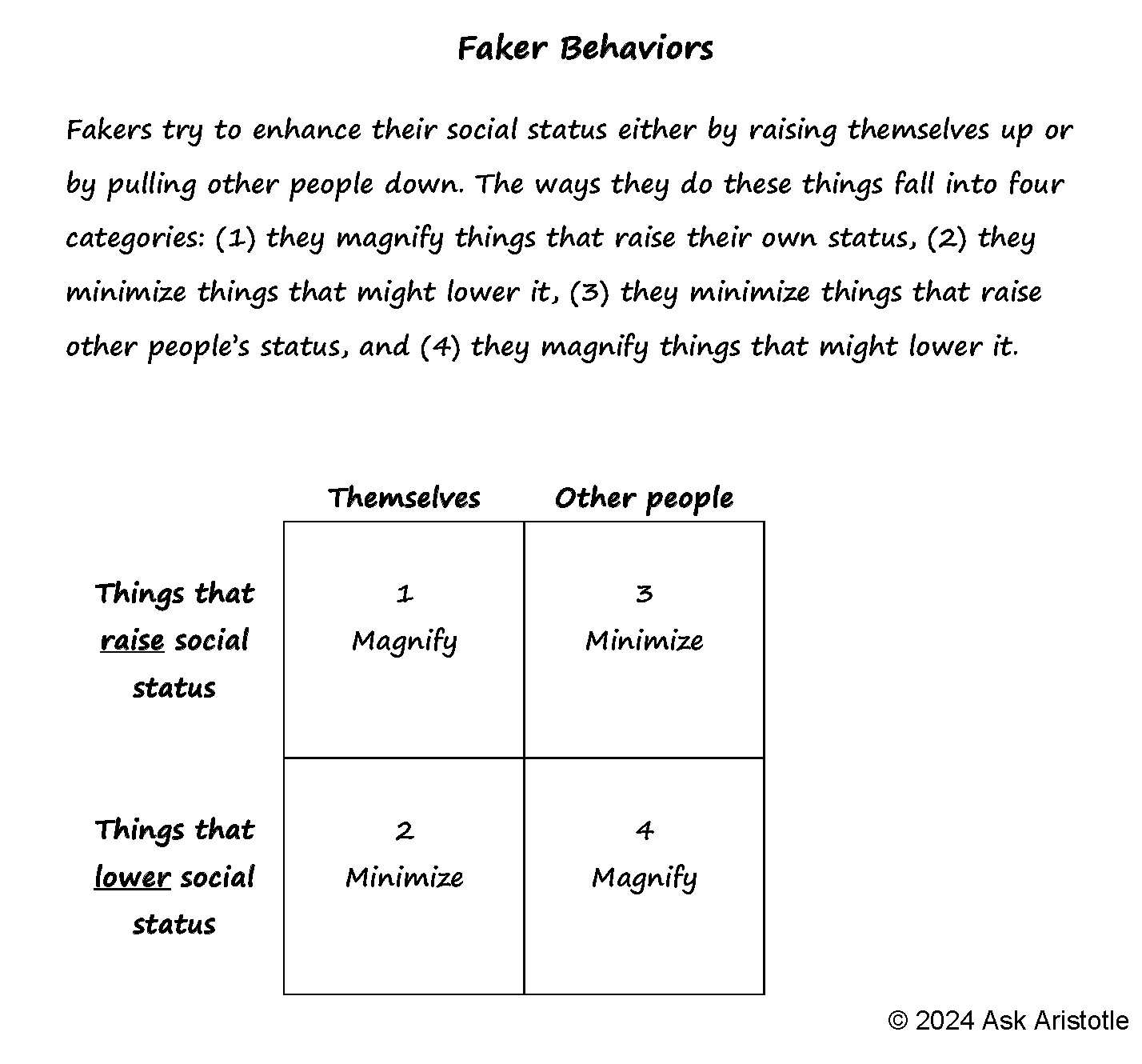

Bill: Faker behaviors belong to four broad categories:

magnifying things that raise their social status,

minimizing things that might lower their social status,

magnifying things that lower other people’s social status, and

minimizing things that might raise other people’s social status.

Vishal: So when you talk about fakers trying to enhance their social status, you’re saying that they try either to raise themselves up or to pull other people down?

Bill: Correct. Fakers want to occupy a high position in the social hierarchy. That means a position above other people. The way fakers see it, they can occupy that position either by raising themselves above other people, or by pulling other people down below them. We can represent how they do these things in a 2x2 matrix:

Vishal: Tell me more about each of the four categories. What are some examples?

Bill: Let’s start with category (1). Behaviors in category (1) include seeking titles and dropping names. Fakers love conspicuous signals of status like titles: VP of this, or Director of that. And they often drop the names of famous people in ways that suggest they have close contact with them: “The other day I was talking to [Famous Name]…” They think that flashing a title or dropping a famous name will raise their social position—that people will hear the title or name and think, “Wow! This person is really special,” and treat them with the deference and respect they crave.

Vishal: I’m reminded of Tim Ferriss again. There are things he calls “credibility indicators”—like having ‘MD’ or ‘PhD’ after your name. He says, “The so-called expert with the most credibility indicators, whether acronyms or affiliations, is often the most successful in the marketplace, even if other candidates have more in-depth knowledge… How, then, do we go about acquiring credibility indicators in the least time possible?” (The 4-hour Workweek, page 184)

Bill: The indicators he’s talking about are conspicuous signals of social status. Magnifying those is a faker behavior in category (1).

Vishal: What else is in category (1)?

Bill: Fakers will often exaggerate or lie about their roles in bringing about good results. They'll take credit for other people's work, or suggest they themselves played a bigger role in contributing to some admired outcome than they played in fact. On the flip side, they’ll minimize the contributions of other people even if those people did the lion’s share of the work.

Vishal: This reminds me of what I’ve seen some managers do. I was once on a sales team. Whenever we had an unusually good sales day, our manager would take all the credit. He’d talk as if it was his decision-making that produced the excellent results—even if he wasn’t there. On the other hand, when our team didn’t do so well, he would never take responsibility. He would instead blame me.

Bill: That story represents a typical faker behavior in category (2). That category includes the many ways fakers try to avoid blame—and not just blame. Fakers also try to avoid accountability, to avoid admitting ignorance or inability, to avoid hard, humble work—to avoid anything fakers think might lower their social status. Fakers are generally more concerned with avoiding these things than with achieving the best results. For example, they’ll avoid admitting mistakes or giving apologies even if that’s the best way of solving a problem or moving things forward. Even when it’s clear they’re in the wrong, they stop short of admitting error. They’ll blame other people, or external circumstances, or bad luck—anything but themselves. When fakers do issue apologies, they’re often fake apologies that exonerate them of any real responsibility: “I’m sorry you felt that way.”

Vishal: That’s interesting. Hearing you describe fakers, I think I’ve encountered a lot of them in my life. The problem is, I’ve found that they’re hard to spot in real time.

Bill: That’s true. Fakers are often hard to spot. The reason is that they tend to avoid high-accountability situations in which there are clear standards of evaluation and clear ways of tracking who’s responsible for what. They sense (correctly) that these are situations in which they’ll be exposed as fakers—situations in which they can’t succeed in taking credit for someone else’s good work, or avoiding blame for their own bad work, or exaggerating their contributions, or minimizing someone else’s. Fakers instead prefer situations in which there aren’t clear standards for evaluating what’s poor or excellent, or in which other people can’t monitor their performance.

Vishal: I’m reminded here of sports pundits. They’ll make all these bold predictions, and they’re often wrong. But there’s no accountability. No one calls them out for being wrong. Instead, they’ll emphasize the few times they’ve gotten lucky and been right, and just move on to making more bold predictions.

Bill: That’s typical of fakers. Fakers generally avoid admitting they don’t know something or can’t do something. Sometimes they’ll pretend to know things they don’t. When they can’t pretend, they’ll mock, criticize, or otherwise disparage the things they don’t know about. It’s their way of saying, “It’s true that I don’t know about that, but that’s because it’s not worth knowing. Someone with my ability or expertise doesn’t need to know about worthless things like that.” On the flip side, fakers will promote the value and importance of the things they do know about, and they’ll fanatically defend the value of their knowledge against any kind of criticism or slight.

Vishal: What’s an example?

Bill: Suppose somebody is faking knowledge of investments. They think their social status depends on looking like they know about money. Then somebody comes along and says, “Hey, what do you think about structured notes?” The faker doesn’t know anything about structured notes. Someone who’s real would be transparent about not knowing: “I don’t know about structured notes. Tell me more.” But that’s not what fakers do. Rather than admitting there’s more to know about money than they know in fact, rather than trying to learn and understand more, they’ll say, “Structured notes are bullshit.” Now, it could turn out that structured notes are bullshit, but to judge accurately that they’re bullshit, you first have to know something about them. Yet the faker doesn’t know about them. The faker rejects them outright. They perceive ignorance as a threat to their social standing. They imagine falsely that experts in a domain have nothing else to learn—that, say, a money expert knows everything there is to know about money. If that false assumption were true, then not knowing something about money would signal lack of expertise. So to protect themselves from that implication, fakers disparage the thing they don’t know about. They act as if it has no value—that it’s not worth knowing. This point about disparaging things they don’t know about illustrates another point: fakers don’t understand how real masters operate.

Vishal: Tell me more.

Bill: Fakers imagine that experts know everything there is to know about a domain—that there’s nothing else for experts to learn. Real experts know that’s false. They know firsthand that the more you learn about a domain, the more you realize how many things you don’t know. The faker hasn’t had this experience. They’ve never done the hard, humble work it takes to gain expertise. So the faker’s image of an expert is exactly that: an image—something the faker has invented in their own mind. They don’t understand what it’s like to be a real expert.

The same point applies to leadership. Fakers don’t understand real leadership. They don’t understand that real leaders lead by example and work harder than anyone. They only notice the fringe benefits of leadership—the social recognition that comes with it. Think of the sales manager you mentioned. If he’d been a real leader, he would’ve worked harder than anyone on your team. But he didn’t. He was a faker.

Fakers generally avoid hard, humble work that builds character and competence over time. They think hard work is for low-status people. As a result, fakers often deflect work. If you ask for their help with a problem, they won’t work to solve it—even if that’s their job. They’ll instead tell you how you can work to solve it. Telling you what to do gives fakers a feeling they really enjoy: feeling like they’re the boss. They imitate the aspect of leadership behavior that they find attractive: telling people what to do. But they imitate without understanding. Their effort is a facade—like a stage set: a simulation of the original without the depth that makes the real thing real.